- Home

- Larry Krasner

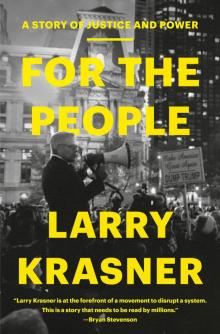

For the People Page 3

For the People Read online

Page 3

Brandon repeatedly knocked me sideways with polite questions that invited no platitudes. He was testing whether I was serious about change, whether I could connect to marginalized people, whether I could manage my end of a campaign, whether I could raise money, and whether I had the stomach for an election that would be an ugly fight and the uglier fight that would come later if I won. I could tell from his questions that Brandon had already studied my career and asked around. As a career trial lawyer, I loved the stealthy questions. He knew his craft and had no tell. I was comfortable on the criminal justice questions. I was off balance on some political questions, but I stuck to what I knew and thought. I was too old to overpromise. I wasn’t sure how my vetting had gone by the time I left, but I knew that if I ran Brandon needed to be on my team.

After I left the office, a few men were standing around admiring my parked red Tesla, an unusual sight that year in Philly. They asked about the mechanics. We spoke for a couple of minutes about the electric car’s mechanics before I got in and drove away. Brandon later told me he and his D.C. colleague were watching through the plate glass to see how I interacted with the men standing near my car in a neighborhood where the candidate they selected would soon have to be comfortable going and getting votes.

Once the campaign was under way, Brandon’s office would consist of a cellphone, a backpack, and a laptop so he could keep moving. He made a point of keeping everybody in the campaign in their lane partly by keeping them out of his, including me, by disregarding my novice candidate questions. Most of the time he came off as stern, a progressive pragmatist and theorist focused on winning elections for the select politicians he believed would actually walk their talk. In a lighter mood most people didn’t see, he was a hilarious, deeply expressive storyteller with a slightly southern flair and a nerdy Civil War historian whose satire of campaign dysfunction and holier-than-thou infighting among liberals and progressives was priceless. As the campaign wore on, I was increasingly aware of how lucky I was to have his experience in organizing and political campaigns.

Jody was slightly older than me, a white career activist and hell-raiser from West Texas, the part I like to call Willie Nelson Texas. I first met her in 2000 when she came to Philly to protest at the Republican convention, liked the city, and stayed. By 2017, Jody was the den mother of all Philly’s activists and organizers, a wise and trusted rock whose twenty righteous arrests for free speech activity layered experience on her deep knowledge of non-violent protest, direct action tactics, and movements. In the world of street protest, notoriously against hierarchy and its trappings, she was still revered—an OG. She also enjoyed treating me like a pesky, slightly younger brother despite the fact that she supposedly worked for me.

My Center City law office, where Brandon and I met on the morning of the announcement, was in two joined antique row houses in the middle of a narrow, historic street in the area old-time residents still call the gayborhood because of its history as a center of queer life and activism. Gentrifying real estate developers preferred to call the area Midtown Village, much to the chagrin of the longtime locals. I’d had my law offices there since 2000, before the real estate developers caught on, when some other lawyers and I bought the vacant building—holes in the roof, water in the walls—with an SBA loan, and began fixing it up.

Brandon and I were sitting in the office lobby on squeaky, tufted leather sofas and chairs by the giant fish tank. I was staring through its glass at the oblivious fish, which looked like a bunch of moving flowers bathed in light, amused by the irony of their aquatic incarceration as we worked on the campaign announcement. I was riffing, rolling through the platform topics with Brandon. Jody and other people from the campaign or from my law office were in and out of my conversation with Brandon. Intermittently, Jody fielded calls and kept the law-firm ship on course. Over several days we had debated whether to announce all the platform’s planks this early, but by the day of the announcement we agreed that we should. Ours was not a personality or experience campaign: It was a campaign of specific ideas that were unfamiliar and even hostile to the status quo. Our voters needed to know that from the jump. With only ninety-eight days to go, there was no time for a slow roll or ambiguity.

The platform summarized the lessons I had lived and learned and heard by listening closely in my time in the justice system. It was what I knew to be true and what needed to happen if we were to move toward a truly just justice system.

We are all equal and deserving of our government’s protection, provided with transparency, respect, and restraint. In such a system, equal treatment is justice. And that kind of justice restores society—restores the relationship between people and government, and makes us safer. Safety and justice are symbiotic and complementary, not trade-offs between opposing forces, as the status quo would have us believe.

Our current criminal justice system is broken; it is unjust and unsafe. Its unfairness and its mad love of retribution have given us a network of mostly hidden gulags that, upon even light inspection, reveal the profound racism of the system that stretches back, largely unchanged, to slavery. This broken system causes crime; it makes us unsafe.

And what is the answer? Where are the nuts and bolts to fix this old, broken car—to change out the parts too dysfunctional to go on so we can keep the rest of the machine moving toward a better place and modernize it yet again?

We need to get people out of jail. Our jails and prisons fail to rehabilitate; often they are so jammed they don’t even try. This means turning away from everything that has caused mass incarceration, including the unnecessary charging of cases, the overcharging of cases, the use of cash bail, policing and prosecution that are lawless and lacking in integrity, and the failure to divert cases away from conviction toward other forms of accountability and rehabilitation. We need to eliminate mandatory sentencing schemes and sentencing guidelines that are too high and that tie the hands of judges, stopping them from doing their job—judging. A death penalty that is unjust, burns money, and never results in executions serves no purpose.

Our broken system also needs prosecutors to stand up for victims, rather than manipulate and use them for political and career-building purposes, only to discard them once there is a conviction and the case file is closed. This requires closely considering and counting the many kinds of victims, their needs, and their trauma. It requires hearing what they say and seeing them as they are, rather than imagining them as traditional and inaccurate stereotypes. Vulnerable victims include sex workers, people suffering from the disease of addiction, innocent people sentenced for others’ crimes, survivors and victims whose crimes are never solved, and immigrants afraid to protect themselves within the system for fear that Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) will deport them. And it requires doing everything in our power to prevent more victimization in the future, by investing broadly as a society in what will prevent serious crime.

By fixing this broken system, we can allow police and prosecutors to focus on the most serious crimes rather than using the ever-widening net they have now for poor people and Black and brown people. That wide net only makes it harder to apprehend and appropriately sentence the much smaller group of people whose crimes tear the fabric of society.

By fixing this broken system, we can save the massive resources spent on unnecessary incarceration and reinvest them in the things that we know for certain actually do prevent crime: education, treatment, job training, and anti-poverty measures, carried out by social workers, public school teachers, and police officers committed to community policing, the annual cost of which is about the same as the unnecessary and destructive incarceration of another human being. This is how and this is why justice makes us safer.

It was what we believed. There were no pollsters to tell political operatives to tell us what we should think, thank God. Even if we had money for them, no thanks. We didn’t want recycled truisms from centrist has-been

s, mainstream journalists, the prosecutors who gave us mass incarceration, or anyone else whose criminal justice knowledge was not learned in their bones, on their block, in their community, or at a criminal justice job that became their life’s work and where the fight they fought was good. We just wanted to say what we wanted to say.

There were some wonderful, smart, and strategic people who knew of our plans to launch a campaign with our full, progressive platform and reached out to preach caution. “Do you really need to mention the death penalty? I mean…are we really trying to win?” We listened to these well-wishers, thought it through, and decided, ultimately, this was no time for caution. Our shot at winning was to tell the truth—the most powerful and exciting weapon in our arsenal, maybe the only one—and see if we could get Philly to join a growing national movement.

Time was getting close. I looked up from my notes again and through the glass that separated the control room from the studio. Brandon and Jody and the rest of the team were out there somewhere in that growing crowd of people, I guessed. It occurred to me it was midafternoon; the day so far had been a blur. I shrugged and rubbed my face, noting the light afternoon stubble. I ducked into the bathroom, checked the already snug knot in my tie, and used water from the sink to plaster down a few unruly gray hairs. I cracked my neck.

It was time. Everything slowed down as I walked the few steps to the brightly lit black box studio. I was crossing a line from lawyer to politician, from sideline commentator to activist campaigner. I headed for the fake wooden podium the studio had wheeled in and was, even now, wiring for sound.

Walking into the studio, I was glad to be surrounded. I felt old for this adventure, but also ready, and my people were with me. If the announcement went well, it would lay out our platform in full, stir up social media, and energize a Philly piece of the movement. If it didn’t go well—if my nerves overwhelmed my trial experience or if our platform fell flat—it would be an embarrassing failure, a defining landmark of my later career, and criminal justice in Philadelphia would go on as usual, unjustly penalizing the poor, the politically engaged, and the powerless. But everyone in that studio had taken wins and losses, so it would be okay. I waited a second for my words to show up.

“Thank you for coming,” I said.

I stopped, took a deep breath, and started talking. Flop or not, here I was. In the next ten or so minutes, I announced my candidacy for district attorney of Philadelphia, and explained our entire platform. I paused occasionally to look around the studio to see if people were leaving or laughing. Everyone was right there. They were looking back, some nodding. When I talked about decarceration, about getting people out of jail, a few shouted encouragement as if we were all together in a lively house of worship. Others joined them briefly. There was some applause; anticipation was giving way to enthusiasm.

I kept an eye on the clock, as I did during closing arguments, trying hard to keep the announcement to about ten minutes. I spoke slowly, paused occasionally, and breathed deeply to ward off my scrambled emotions. These were useful tactics I had learned from watching other lawyers whose jobs required their standing before juries that would decide whether or not to execute their clients—or whether their clients were even guilty. There was an economy of words, an unhurried pace. I managed my emotions and nerves well until about nine minutes and thirty seconds in, when I was wrapping up my speech thanking the many lawyers, activists, and organizers in attendance who had for so many years fought “the good fight.”

And then, suddenly and for a moment, when I heard myself say those words I choked up. What I saw moved me: A circle of people facing one another who had chosen throughout their lives to take the hard way, to make trouble, to bear the abuse heaped on them by the insiders and their institutions that would later reap the benefits of reform at no real cost to themselves. I had watched these people do battle in “the good fight” for others who couldn’t easily fight for themselves. Having these fighters surrounding me in a circle—these activists and advocates and angelic warriors—so attentively staring back at that moment humbled me, and started to make me wonder if we would win. I concluded by asking everyone in and outside of that room to “join us.” I checked my watch: ten minutes on the nose.

I called up my campaign chair, the activist lawyer Mike Lee, whose buoyant, youthful optimism and humor were reflected in his bright floral bow tie and especially bright smile. Mike ended the event with a quick list of next steps and a call to action. I knew that Mike and his partner were expecting their first child, whose gestation and birth would overlap and coincide with the campaign. Then came a circle of powerful applause, including mine, for everyone else there.

The announcement video spread quickly on Facebook in Philadelphia, including my choke at the end of the speech. Within a few days, the announcement video’s views far outnumbered those of the slick commercial that Dick Rubio, supposedly a leading candidate, had been circulating for months. His ad was a high-resolution scare tactic, a shadowy three-minute piece that showed him all over the city looking and sounding like Batman making Philly Gotham safe for little boys wearing football uniforms (a detail to remind us that Dick had briefly played pro football, as if that mattered). Dick’s professional commercial, which included no real platform, got a couple thousand hits in three months. Our low-tech video was a stationary shot from a single camera in a black box studio of a fake wood podium and a talking head—mine. Within one week, more than twenty thousand people had viewed our video. We could feel the ground moving under us because we said something, and because activists do what they do.

One day after the announcement, the news hinted that Seth Williams, the incumbent DA who was seeking reelection, was about to be indicted in federal court on corruption charges for improperly accepting gifts he did not disclose as the law required. The timing was surprising, earlier than expected, although everyone knew that Williams was under investigation. Most people expected that he would face whatever might be coming after he was reelected. Only three days after my campaign announcement, Williams ended his campaign for a third term. Within months he was charged with crimes. Ultimately, he was sentenced to five years in federal prison. But on that day, the day he withdrew from the race, every current and wannabe candidate knew the election was wide open. I was the sixth candidate to declare; soon enough there would be a seventh.

I was an older, unlikely novice candidate running as an outsider against insiders. My team and I were doing things our way, regardless of the consequences—and we started late. It was time to go looking for our voters, with only ninety-eight days to go.

CHAPTER 2

Early Outsider

You get mistaken for strangers by your own friends

When you pass them at night

Under the silvery, silvery Citibank lights

Arm in arm in arm and eyes and eyes, glazing under

—The National, “Mistaken for Strangers”

I’ve introduced you to some outsiders at our campaign announcement. Now let’s talk about what made me run. Law and politics are dominated by insiders: people who work in rooms and go home to neighborhoods that most of the rest of us will never know. Even the most well-meaning politicians often live far away from the life experiences of the people they serve. But there’s no law that says politicians have to be rich, or to come from political dynasties, or to be connected to power players and in service to them. There’s nothing about wealth that says anything about the wealthy besides that they were lucky, maybe from birth or before—they are not necessarily smarter, harder working, more humane, more resourceful, or more resilient than anyone else. We all know this intuitively, but the play of luck and misfortune in our own lives is our strongest lesson in this truth. The trick is making sure we don’t forget it.

When I was about eight, I was watching cartoons in our living room one afternoon when my dad opened the front door of our recently bought, basic Philly

-area two-story home. It was after school, but he was home from the office early. He wore a dark gray suit that matched his silver hair, big black “gunboat” shoes, as he called them, a white shirt, and a skinny dark tie. My dad was a funny man who liked to fake being a curmudgeon, and I waited for him to say something amusing, or just something, as he usually did when he walked in. But he limped across the living room, not even looking in my direction, and disappeared quietly into a first-floor bedroom, where my mother was waiting for him. They closed the door.

I went back to watching cartoons, a little distracted. I could hear my parents speaking but couldn’t tell what they were saying. When my dad came out, his face was flushed. My mom walked out after him, and I heard her saying as she followed, “God will provide.” My mother was a woman of deep Christian faith—a former tent evangelist and seminary student—and this was the kind of hopeful thing she would have said to a firing squad from the crosshairs. I forgot the cartoons. I knew there was trouble and, even more alarming, that my parents were trying to shield me from it. It felt like someone had yanked a blanket off and suddenly everything was a little colder and less certain.

After that day, my dad mostly worked from home. Even at eight, I knew that jobs worked in an office funded by someone else, the kind you dressed up for in a suit and polished shoes, were the ones with steady pay. In 1970, my dad’s daily working from home in casual clothes was another signal to me that we might need some help.

My parents were older than anyone else’s parents I knew. Dad was forty-five when I was born; Mom was forty. They had weathered the Great Depression, early jobs and careers, World War II, higher education, and next careers before they found each other. By the time I was born, Dad was increasingly bothered by arthritis, especially in his hips, and jungle rot in his toenails from serving in the Pacific during the war.

For the People

For the People